Experimenting…

What comes to mind when you hear the word “experiments?”

Maybe it’s footage from an old Frankenstein movie, or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Maybe it brings up emotions of fear and distrust, like for many people of color who know about the awful history of the Tuskegee Study. As a kid, I used to love going down into my grandma’s old basement and mixing things together to see what would happen (thankfully I never managed to develop any explosives). And yes, I did have a chemistry set as a little girl. Not surprisingly then, as someone who has spent much of my adult life thinking about and doing experiments (clinical studies) that answer questions about how to improve health care, the word experiment for me is linked with feelings of creativity and exploration. Maybe that is one of the reasons that I came to love natural dyeing, since the process of experimentation is so foundational to this work.

Whether you approach experimentation in natural dyeing more qualitatively (just trying something out and then describing what you did in words or pictures) or quantitatively (designing specific steps and recording results of each step), keeping track of the results of your work is really important to your own personal learning and growth.

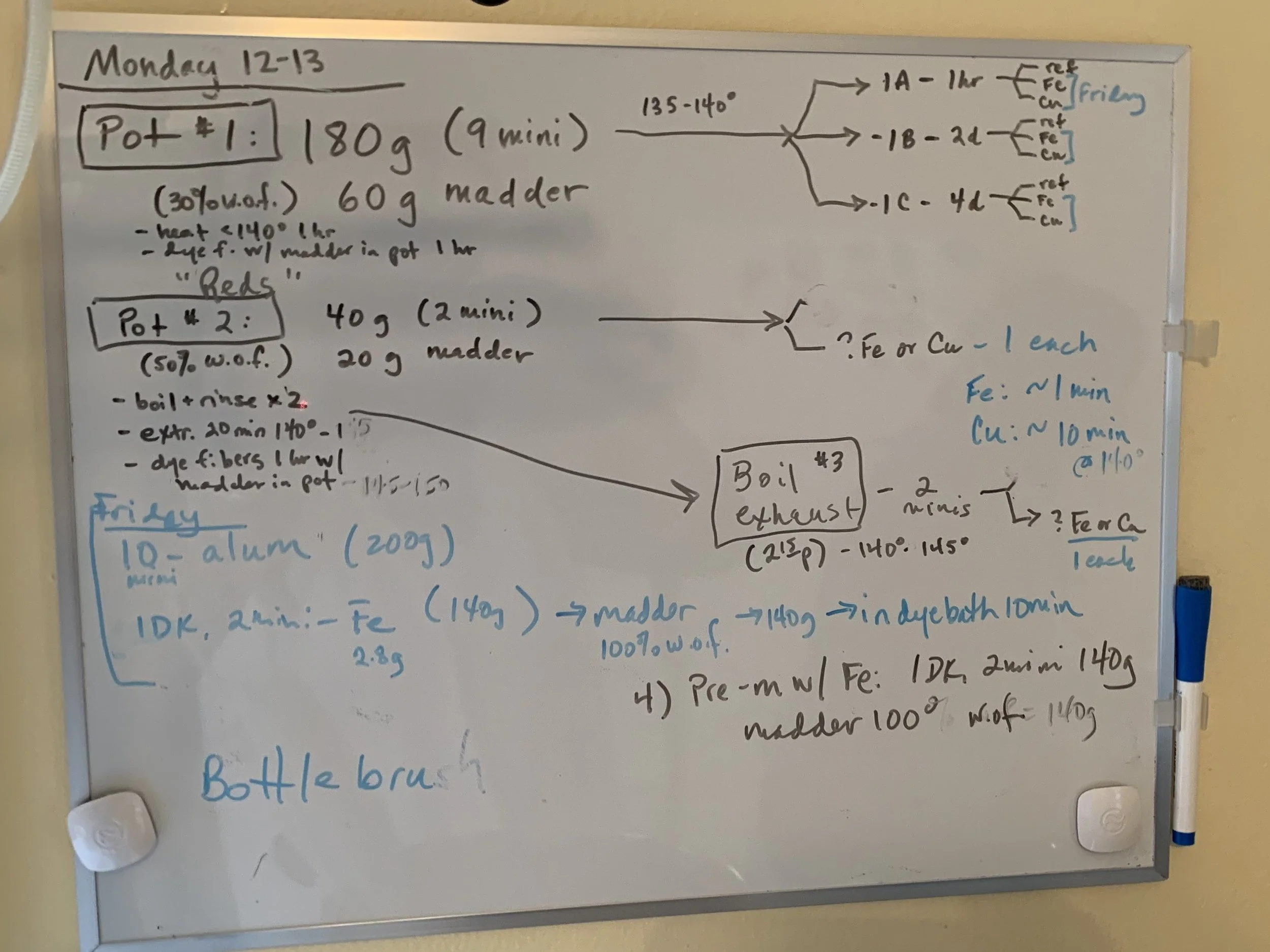

In our studio things can happen fast, so keeping track of what we are going can be a challenge and it often takes different forms. Sometimes we jot down a short description of what we are doing, or some measurement like temperature or pH of a dyebath, on a whiteboard and take a picture of it as a way of recording what is happening in the moment.

Sometimes we plan out an experiment ahead of time using a paper form we developed and write down the results (and any alterations to the plan) more methodically as we go.

Will we remember all this later?

This works especially well if we are doing an overdyeing experiment and need to keep track of which skein had which strengths of dye in each step (this is how we would use the blanks for Pots 1-4 in the picture).

We do make frequent use of a digital thermometer and a digital pH meter as well (I am especially fond of the pH meter, which brings me back to my old college lab days).

We *may* have gone a bit overboard when we did a 3-way experiment with cochineal and pH, examining whether the method of reducing pH (vinegar or a citric acid solution) and whether the method of dyeing (in a pot held to temp or in a jar in a roaster) affected the color result of 3 different cochineal weights of fiber (the matrix table was beautiful though, we promise!). And if you are interested in the results: TLDR, neither the method of achieving the pH or the method of dyeing affected the color on any of the different weights!

We’ve found it useful to record our experiments in a spreadsheet—we include the date, the dye material, the fiber material, amounts, and processes. That way we can more easily match up pictures we’ve taken or actual yarn samples with the recipes we have recorded. We can also look back at the experiment notes if we have forgotten exactly how long we extracted that madder, and at what temperature, for example.

The notebook…

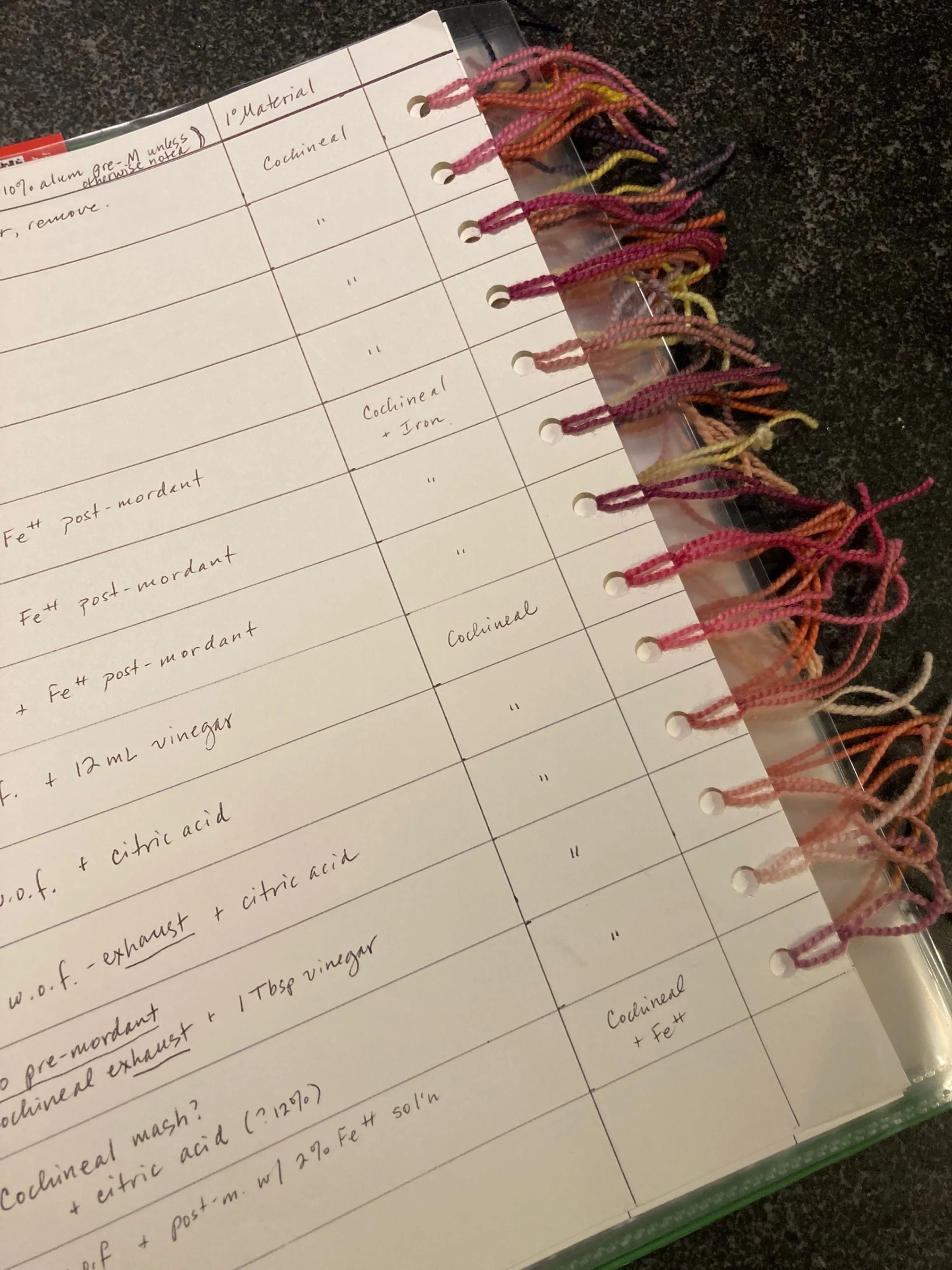

If we have found a color we want to reproduce, we also record the experiment in a spiral notebook that is organized by color group, with a brief description and a piece of the actual test yarn—this is really helpful when we are trying to put together a specific palette or a colorway and want to compare different recipes we have used to get a specific shade. We also include the paper experiment log (if there is one) for these recipes we want to reproduce just in case there are extra notes there that didn’t make it into our spreadsheet.

And there are other experiments to record as well beyond just the dyeing part—a major one of these is lightfastness, or how much a given color from specific dye material(s) tends to fade in natural light.

Lightfastness test of logwood plus cochineal

Some dye materials like logwood are known to be less lightfast, so below is an example of a test we did to see how much the addition of varying amounts of cochineal (a more lightfast dye material) affected the lightfastness of the logwood.

Michelle’s cochineal-tannin fiber experiment

So whether you are more of a “happy accident” sort of dyer, or a “plan it out first” sort of dyer, be sure to record what you are doing in whatever medium fits naturally into your way of doing things, and know that lots of great learning can come from this practice. Happy experimenting!